Motor

- heat engine (internal combustion(IC): steam, disel, gasoline)

- complex, heavy, big, expensive

- maintenance

- wearing out

- 75% of efficiency

- non-renewabable enrgy

- non-health exhaust

- Co2

- electric engine

- simpler construction (one moving part - rotor)

- loght, compact, cheap

- energy efficient (100%)

- lasts forever

- no exhaust

Fuel

- stores a lot of energy in compact way

Battery

- way worth storage of energy than fuel

- in practice does not mater much 🤔

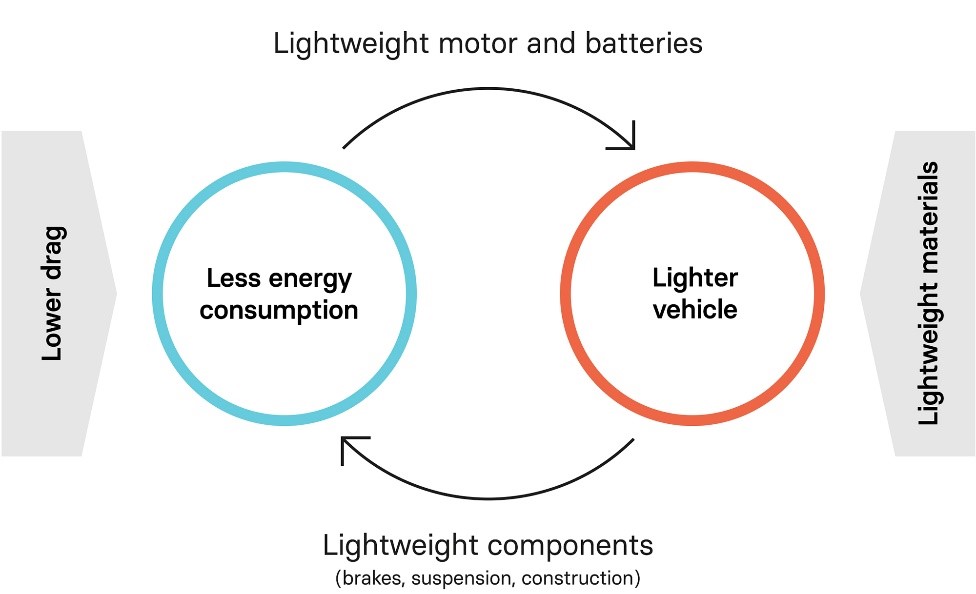

- weight of batteries is evolutionally reducing

- leads to cheaper vehicles

- generates a lot of heat

Six errors when comparing CO2 emissions

- Overestimating battery manufacturing

- Underestimating battery lifetime

- Assuming an unchanged electricity mix over the vehicle’s lifetime

- Using unrealistic tests for energy use

- Excluding fuel production emissions

- Lack of system thinking

Types of vehicles

- Hibrid EV - EV + IC = recharges battery on braking

- not nuch useful

- not much power comes from electricity

- Plugin Hybrid = uses both elecric engine with battery and ICE

- complex

- Full EV

- cheaper

- low maintenance

- pedal driving with regeneration

- Hydrogen Fuel cell

- smaller battery

- refueling is fast

- efficiency is lower than FEV

Motors characteristics

- Electrotechnical

- Mechanical

- Practical

- Economic

- Environmentsl

Motor types

- DC brushed

- Induction (basic)

- no brushes, more control

- industry standard

- async

- Permanent Magnet Rotor (best performet)

- sync

- less heat and losses

- the best

- needs expensive metals

- Sync Reluctance Motor (best all around)

- good efficiency

- cheaper, no magnets

- noice

Power electrnics in EV

- Power elect convertor

- power elec switch - turn on and off frequently

- Converts AC (Alternating Current) -> DC (Direct Current) and back

- Magnetic Isolation — yes/no

- Bidirectional Power flow — bdirectional or unideirectional

Regen braking

- ICV turn kinetic energy to heat using braking system. Non recyclable.

- EV return this energy to batteries

- reguces energy consumptions

- longer range

- less maintenance

Limits

- limited by power and speed, so cannot be exclusively used

- limited to axle where the motor is connected

Range

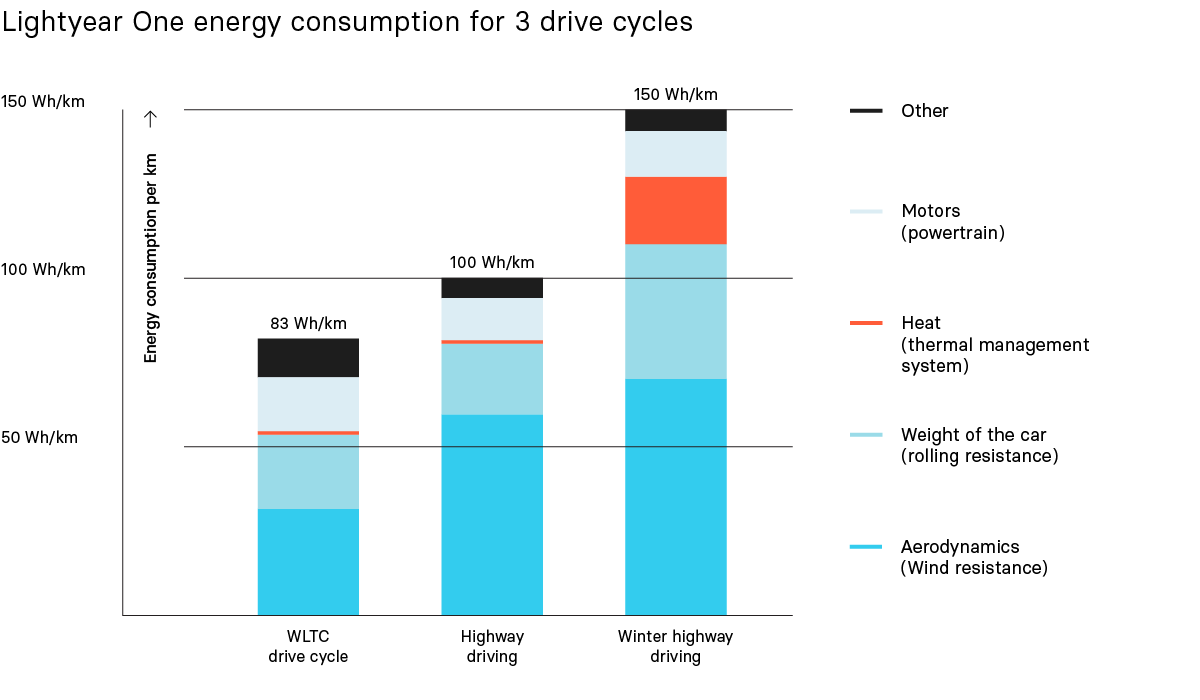

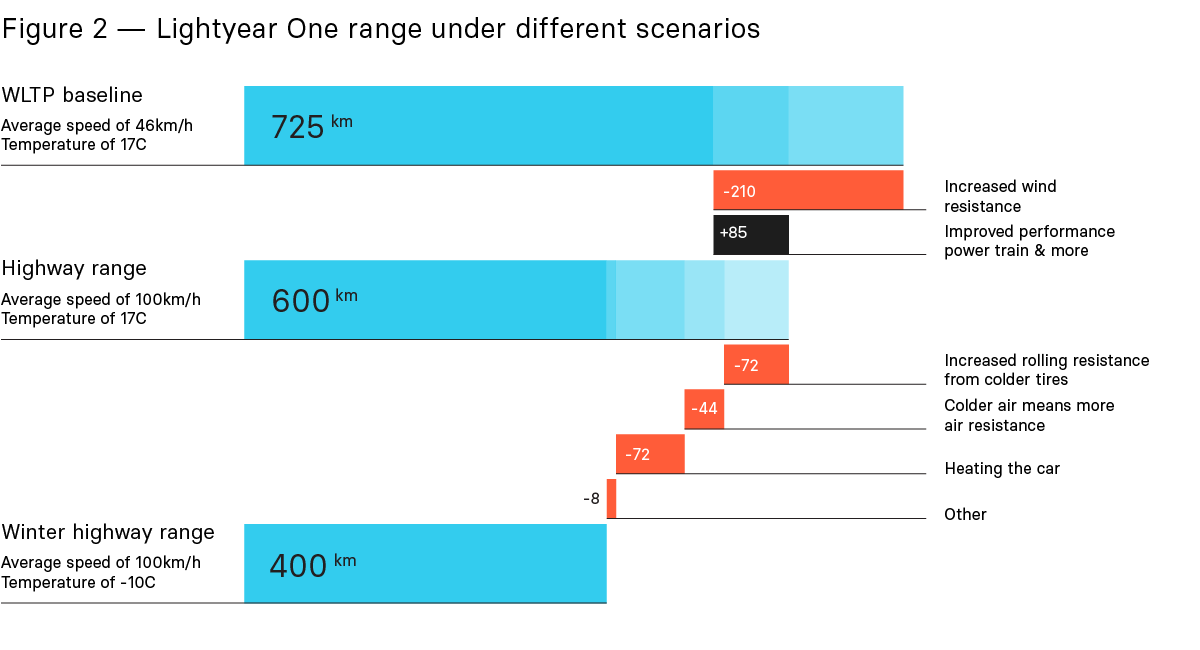

Factors that Affect the Range of an Electric Vehicle

-

Temperature: Nearly 60% of the fuel that enters the ICE in fuel-powered cars is used to produce heat

-

Rolling Resistance: The main source of EV energy consumption at low speeds is rolling resistance. When EVs carry heavy batteries – more energy is needed to drive for significant ranges.

-

Wind Resistance: The faster a car moves, the more air it has to move through and the more energy it wastes to get through the wind.

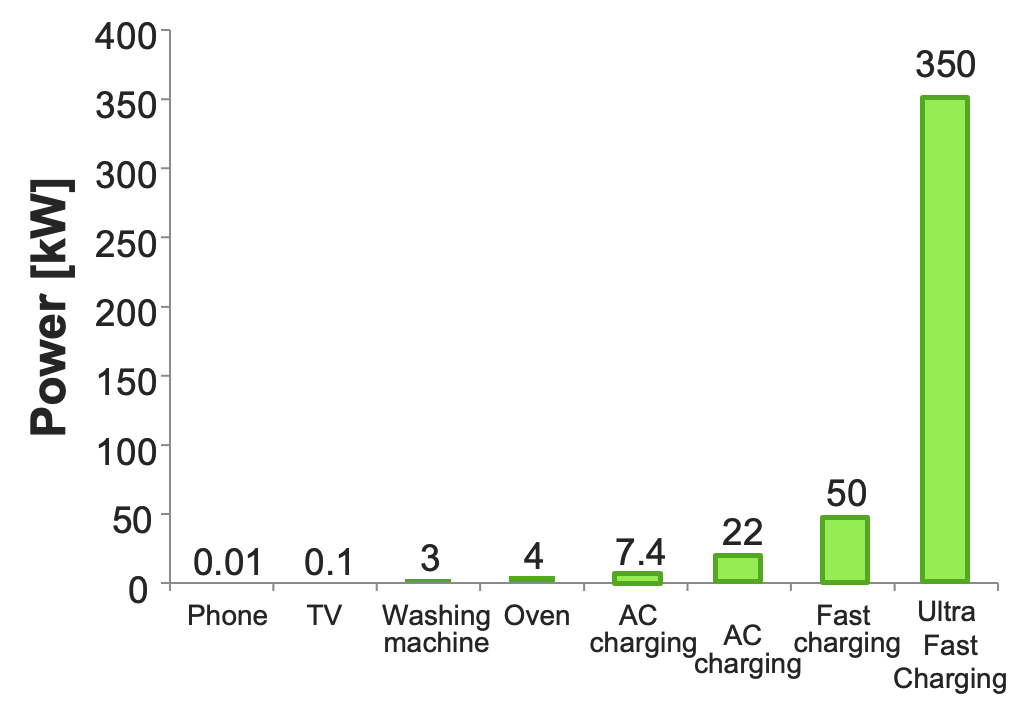

Charging

3 ways:

- Conductive chagring

- AC

- anywhere, standard

- BMS easy communication

- gotta be converted to DC in the car

- needs long time

- DC

- high power

- fast - less that 1h

- not limited with weight and size

- difficult to install

- difficult during peak hours

- supply network restrictions

- AC

- Inductive

- less cables

- safer in weather conditions

- hight invest

- limited space

- misalignment

- induction loss

- possibility of dymanic charging (under the road emitters)

- longer battery live

- Battery swap

- in a bay, automatically

- difficult to get market acceptance

- no standard

- no way to estimate battery health

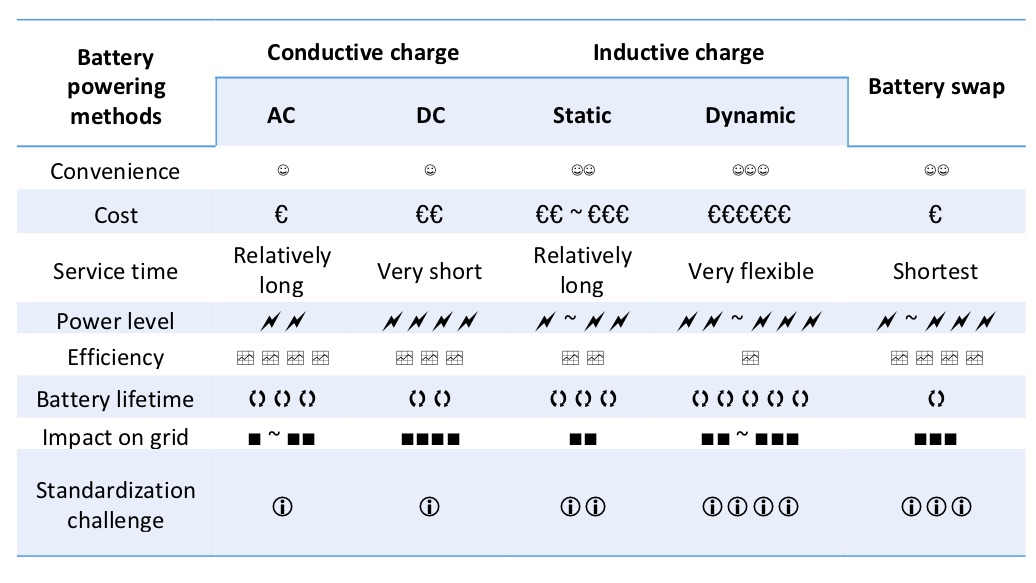

Overview

- It can be observed that dynamic inductive charging is the most convenient charging method but also the most expensive. Even if the static inductive is cheaper compared to the dynamic one, the average cost of inductive charging is higher than any other method. Dynamic inductive charging has the most flexibility as the car can be charged at any time when on the way and does not need to stop by the service point.

- To power the battery, the battery swap method needs the shortest serving time. For all charging methods except battery swap, the serving time is highly related to the power level. In this case, the DC conductive charging method has the highest power capacity among all the methods.

- There are many factors that impact the efficiency, e.g. the number of power converters and their types, the charging power, and the charging methods. From the table, we can see that, in general, the conductive charging method has higher overall efficiency than inductive charging. It is because the power conversion process using an air gap is less efficient than direct power transfer using cables. Further, the efficiency of inductive charging reduces as a result of the misalignment between the sending and receiving charge pads.

- The battery lifetime depends on many factors, for example, the charging power (C-rate) and the DOD. The battery lifetime in DC charging has the lowest lifetime because the charging power and hence the corresponding C-rate are the highest. Further, typically at fast charging stations, people want to charge their batteries as much as possible for long-distance trips increasing the depth of discharge as well. On the contrary, batteries operated with the dynamic inductive charging method have the longest lifetime expectations because the batteries can be charged/discharged with a small DOD.

- From the perspective of grid impact, the DC charging method has the most significant impact since it has the highest power level. Besides, the battery swap could also have a high impact on the grid if the charging powers are high as well.

- Finally, considering the standardization challenge, dynamic inductive charging and the battery swap are faced with the most difficult challenges. It is because both methods require standardization between car types, battery size, power level and even shape.

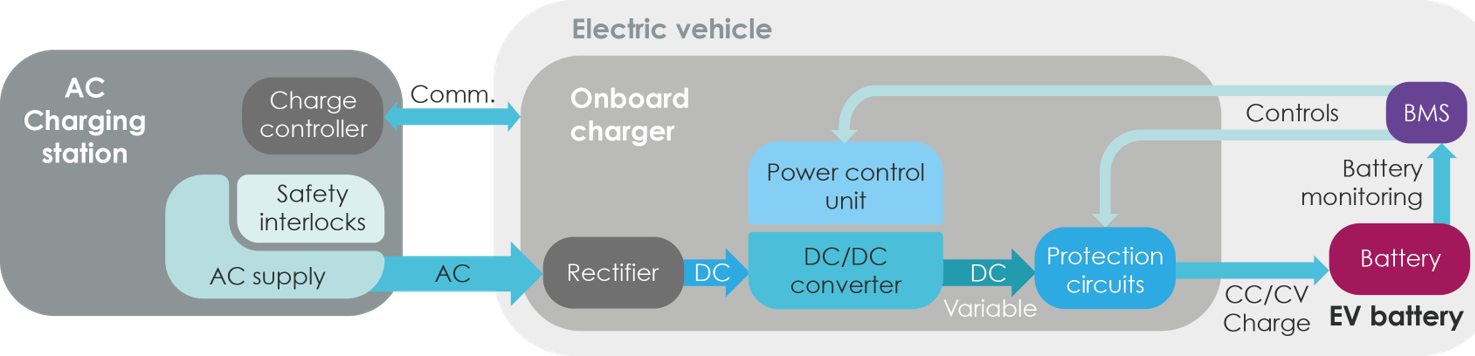

AC charging

- When the charging station and the EV are first connected, the charge controller in the station communicates with the EV. Information regarding the connectivity, fault condition and current limits are exchanged between the charger and the EV.

- When the AC power is provided to the EV, the onboard charger has a rectifier that converts the AC power to DC power. Then, the power control unit appropriately adjusts the voltage and current of a DC/DC converter to control the charging power delivered to the battery.

- The power control unit, in turn, gets inputs from the Battery Management System or the BMS for controlling the battery charging.

- Apart from this, there is a protection circuit inside the onboard charger. The BMS triggers the protection circuits if the battery operating limits are exceeded, isolating the battery if needed.

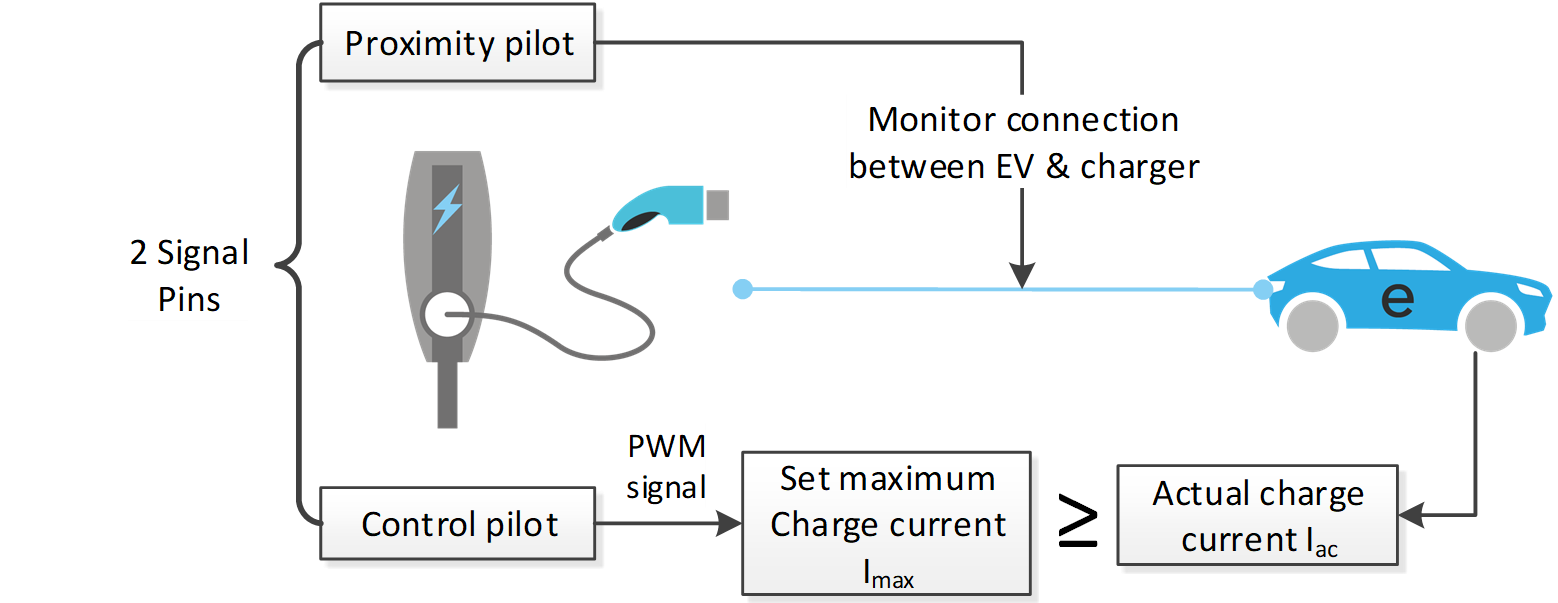

### Control and proximity pilot

- The Type 1 and Type 2 connectors have 2 common communication pins: the Control Pilot (CP) and the Proximity Pilot (PP).

- The Proximity Pilot (PP) checks if the vehicle connector is connected properly to the vehicle inlet. If the connection is not properly established, the Proximity Pilot will detect it, and the entire process will be disabled for safety.

- The second special pin is the control pilot (CP), and it is used for controlling the charging current. The control pilot continuously sends a pulse width modulated or PWM signal to the car. In this way, it tells the car the maximum current that can be drawn from the charging station. The car then can draw the desired current , as long as this value is smaller than the maximum current.

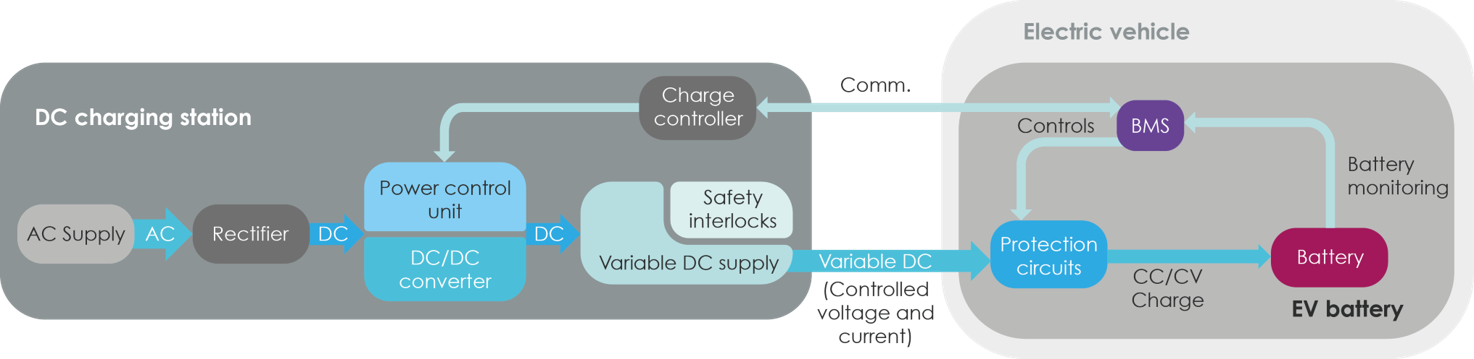

DC charging

- In the first step, the alternating current or AC power provided by the AC grid is converted into direct current or DC power using a rectifier inside the DC charging station.

- Then, the power control unit appropriately adjusts the voltage and current of the DC/DC converter inside the charging station to control the variable DC power delivered to charge the battery.

- There are safety interlock and protection circuits used to de-energize the EV connector and to stop the charging process whenever there is a fault condition or an improper connection between the EV and the charger.

- The battery management system or BMS plays the key role of communicating with the charging station to control the voltage and current delivered to the battery and to operate the protection circuits in case of an unsafe situation.

Limitations of fast charging

- Higher charging current leads to higher overall losses both in the charger and in the battery. As the charging currents increase, the effective capacity of the battery decreases as well (for example, as given by Peukert’s law).

- The battery C-rate increases with fast charging, and this reduces the battery life due to the heat produced and increased degradation due to the higher temperature.

- When fast charging a battery, the SOC of the battery can only be reached 70-80%. This is because fast charging creates a lag between the voltage and state of charge, and this phenomenon increases as the battery is charged faster. Hence, fast charging is typically done in the constant current or CC region of the battery charging, and after that, the charging power is reduced in the constant voltage or CV charging.

- For any EV charger, it is important that the cable is flexible and lightweight for people to use and connect to the car. With higher charging power, thicker cables are needed to allow more charging current, else it will heat up due to the losses. In the future, with currents above 250A, the charging cables will become heavy and less flexible to use. The solution would be to use thinner cables with cooling and thermal management to ensure that cables don’t heat up. This is, of course, more complex and costly than using a cable without cooling.

EV impact on the grid

- Overload: The higher EV charging demand will increase the loading of the cables, lines, and transformers in the transmission and distribution network, possibly overloading these assets if the peak demand of EVs coincides with the existing peak on this grid.

- Voltage problems: In the case of networks with long feeder cables, then the high demand of EVs coupled with distributed generation can cause overvoltage or Undervoltage to specific customers located close to the end of the feeders

- Phase imbalance: In the case of 3 phase network, imbalanced EV charging loads on one or two phases will cause phase imbalances that might be challenging to rectify from the grid operator side.

- Harmonic injection: Since EV chargers are power electronics devices operating at high powers and high switching frequencies, they can inject harmonics, inter-harmonics and supra-harmonics into the grid depending on the frequency of the harmonic with respect to the fundamental frequency. This can cause unnecessary resonance resulting in distortion of the grid voltage, flickering and heating of appliances

Smart Charging

Benefits of smart charging:

- It can increase the flexibility of charging by controlling the charging power, charging time duration and charging power flow direction.

- With the high charging flexibility, the utilization rates of fixed assets like transformers and power lines can be higher, which also helps in reducing the cost of EV charging.

- Smart charging can increase the efficiency of power transfer and help reduce the peak demand on the distribution network.

- EVs can be made more sustainable by charging them based on solar and wind generation. Moreover, smart charging can provide new revenue streams to EV owners, like providing frequency regulation and vehicle-to-grid services.

Four degrees of freedom to implement smart charging:

- Charging power: the magnitude of charging power as a function of time.

- Time flexibility: decide on when to charge the vehicle and when not to.

- Charging direction: unidirectional or bi-directional.

- Fast ramp rates: the charging power magnitude can be changed in the order of milliseconds.

V2G

The key benefits of vehicle-to-X (V2X) include:

- It acts as an energy storage medium thereby allowing for better management of variability and greater deployment of renewable energy solutions.

- During periods of high demand, the battery in an electric vehicle can be for peak shaving by feeding energy back to the grid.

- It serves as a backup energy source during blackouts or power failures.

- Vehicle-to-X (V2X) can also be used to perform ancillary services such as frequency and voltage control. This gives an electric vehicle user a much more potent revenue stream than smart charging.

For all its benefits, vehicle-to-grid implementation faces some key obstacles such as:

- The bidirectional chargers required for these applications are larger and more expensive than unidirectional chargers.

- Vehicle-to-grid (V2G) applications result in a greater number of charge and discharge cycles of the battery in an electric vehicle. This increases the degradation that the battery undergoes.

- The infrastructure, standardization, regulatory framework and financial incentives essential for the implementation of vehicle-to-X (V2X) applications are still under development.

ICT

Further reading

- G. R. C. Mouli, P. Venugopal and P. Bauer, “Future of electric vehicle charging”, 2017 International Symposium on Power Electronics (Ee), Novi Sad, 2017, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.1109/PEE.2017.8171657

- https://www.zap-map.com/charge-points/

- https://www.afdc.energy.gov/fuels/electricity_stations.html

- Emissions Associated with Electric Vehicle Charging: Impact of Electricity Generation Mix, Charging Infrastructure Availability, and Vehicle Type Joyce McLaren, John Miller, Eric O’Shaughnessy, Eric Wood, and Evan Shapiro National Renewable Energy Laboratory https://www.afdc.energy.gov/uploads/publication/ev_emissions_impact.pdf

- Enabling Fast Charging: A Technology Gap Assessment, US Department of energy, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2017/10/f38/XFC%20Technology%20Gap%20Assessment%20Report_FINAL_10202017.pdf

- Several interesting publications on EV charging can be found at https://www.afdc.energy.gov/publications/search/keyword/?q=electric%20vehicle%20charging